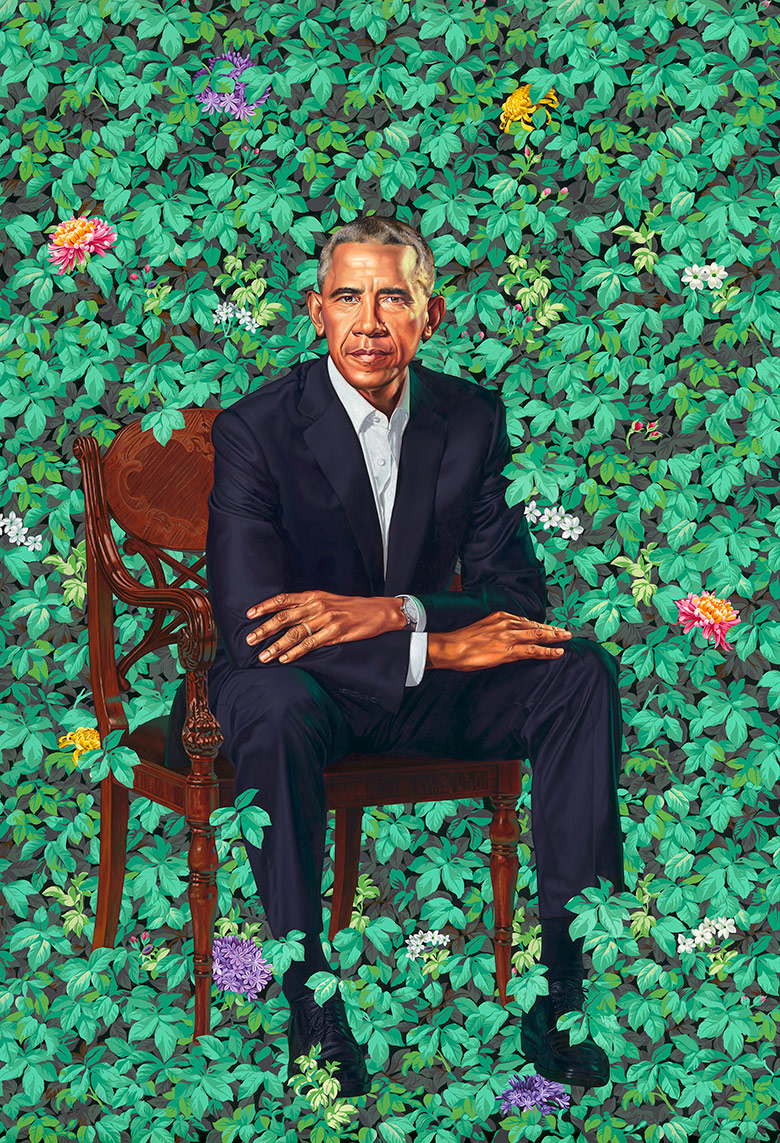

By Kehinde Wiley

By Amy Sherald

Psalm 1: Slow Dance by Steve A. Prince

FORBES

Discovering talent in the explosive world of online art has never been easier. Finding details on pricing, however, remains elusive. Over time, this series will serve as a pricing database for creatives across the globe. For now, let’s take a journey into the studios of twelve artists, from Jackson Hole to Madrid.

Amy Ringholz’s Studio © Amy Ringholz

Artist Name: Amy Ringholz

Location: Jackson Hole, Wyoming

General Price Range: $5,000 – $25,000

William Kwamena-Poh in The Studio © William Kwamena-Poh

Artist: William Kwamena-Poh

Location: City Market Art Center, Savannah GA

General Price Range: $550 – $15,000

Kerry Irivne Montauk Studio © Matt Albiani

Artist Name: Kerry Irvine

Location: West Village, New York

General Price Range: $900 – $15,000

Daniel Maidman’s Studio © Daniel Maidman

Artist Name: Daniel Maidman

Location: Brooklyn, New York

General Price Range: $2,200 – $13,000

Adam Turman’s Studio © Adam Turman

Artist Name: Adam Turman

Location: Minneapolis, Minnesota

General Price Range: $3,000 – $15,000

Lena Rushing in The Studio © Lena Rushing

Artist Name: Lena Rushing

Location: Grover Beach, California

General Price Range: $400 – $6,000

Carmela Alvarado in The Studio © Aitana Merino

Artist Name: Carmela Alvarado

Location: Madrid, Spain

General Price Range: $500 – $11,000

Evan Venegas’ Studio © Evan Venegas

Artist Name: Evan Venegas

Location: Ridgewood Queens, New York

General Price Range: $150 – $6,200

Kieran Madden in The Studio © Kieran Madden

Artist Name: Kieran Madden

Location: Brooklyn, New York

General Price Range: $400 – $1,200

Scott Kahn’s Studio © Scott Kahn

Artist Name: Scott Kahn

Location: Dumbo, Brooklyn, New York

General Price Range: $4,500 – $25,000

Steven Tiller in The Studio © Steven Tiller

Artist Name: Steven Tiller

Location: Sacramento, California

General Price Range: $2,000 – $16,000

Barbara Krupp’s Studio © Barbara Krupp

Artist Name: Barbara Krupp

Location: Oak Harbor, Ohio

General Price Range: $1,800 – $14,000

Dr. Saint James.......interview.......awesome artist.

Scorpio ~ Rebirth Of The Phoenix

Framed original oil painting 20"x24" on sale $1400

Program helps area students plant SEEDS for their futures

August 7, 2013Updated Aug 7, 2013 at 10:25 PM CDTPEORIA, Ill. -- A state funded program is planting a seed into the future for several local students.

They are getting early exposure to careers under a summer employment program.

On Wednesday, Brandon Ruffin, 16, was lending his hand and skills on a project at Infrastructure Engineering in downtown Peoria. The Peoria High School junior wants to be a mechanical engineer.

"The first week they had us like using this program to like design stuff and now she got me designing pipes for a Chicago project,” said Ruffin. “It's kinda hard but it got easier as you learn stuff.”

Ruffin is among 25 local students taking advantage of paid internships with local companies under the Social Educational and Employment Development Services Initiative also called SEEDS.

"They get to experience things that normally they would not get to experience, working with engineering firms, working with an artist, a doctor,” said Kenyatta Fisher of the Illinois Black Chamber of Commerce.

Over at the Jonathon Romain Art Gallery, four students were helping Romain put in a window in the front of his studio. The task at hand is more labor intense and with not as much focus on the prints inside his massive gallery.

"What I don't think is that they will leave disillusioned about being an entrepreneur and it being easy,” said Romain. “I think they will see that it takes a lot of hard work."

"Being here just exposed me to more art,” said SEEDS participant Malik Gillum. “At first I really didn't like art, but being here I know how to do multiple things now."

For aspiring young artist Kendrick Ingram it's also a chance to get his work critiqued.

"It feels good, I can bring my art and he'll give me pointers on it,” said Ingram. “These paintings tell me that my work got to mean something and it has to have some type of meaning behind it."

Ingram said the internship has left an impression he will paint well into his future.

June 2013

It's not much of a leap to think about Los Angeles as a medium in and of itself -- some tool or substance an artist might pick up and utilize in someway -- like the remainder of a fabric bolt or a found roll of yellowed paper already haphazardly scissored through.

As a visual artist, Michael Massenburg has long viewed the city as his own vast supply hutch -- both the physical expanse of it and the cast-off-detritus he might happen upon in the course of a day. "I've got to be careful," says Massenburg, on a recent afternoon, winding past some of his stored pieces leaning against walls and baseboards. There's a discarded Mid-Century wood-console stereo that he remade into "Sounds of Life," a paean to jazz, soul R&B -- its surfaces and interiors papered with vignettes, paintings, photographs, collage, two-dimensional stolen moments of music's bygone era. Nearby, leaning against a wall is a floor-to-ceiling generational mural, "Memories of Dreams Past, Part 2," composed on an oversized a disk, now sectioned to fit within doorframes -- that for a time sat within the courtyard of the California African American Museum. "Really, I can't take anything more in," he says. "There isn't room, at home or at the studio." As it turns out, we are still only in the common area of this warehouse space in Inglewood, his studio still a few steps around the corner -- "Friends start saving stuff: "Hey Mike -- You interested in this? How about this balled up piece of paper?'"

"Sounds of Life," by Michael Massenburg.

"Sounds of Life (detail)," by Michael Massenburg.

This admission doesn't accurately portray the world inside this room. While there might be an explosion of inspiration lining the studio's shelves and walls -- books, photographs, splintered pieces of wood, a stretch of canvas, discarded signage, recycled museum wall-text panels -- there is a keen sense of organization and unified purpose in Massenburg's collections -- both the found objects and in the work itself. Truth is, he explains, "I love stuff when it is already broken, because I can kind of bring it back to life."

As an artist, he is also trying to piece together potentially fading memories, misplaced histories -- stories about people and stories about place -- in a region where the narrative is often interrupted -- sections rearranged, re-thought, sometimes entirely elided.

Over time, he has noted, the freeways in particular have snipped away connections -- edited a sense of the progression of the city, its very connective tissue: "People say I don't pass this or 'I won't go past this street." Such arbitrary self-editing lends an erratic, disconnected understanding to the idea of a place. Whole swaths of L.A. are avoided and consequently unknown: "Inglewood is actually part of the South Bay -- but I guess it got kicked out, " he cracks. "This" -- he gestures expansively toward the street just beyond the warehouse's open doors -- "is 'South Central.' Look, now, I've lived in both places and they are completely different in terms of dynamic, but it's funny how its all lumped together because of culture and race. It's all about perception."

Michael Massenburg | Photo: Marlene Picard.

What's discarded versus what's valued is also perception, Massenburg knows. In telling stories, by way of discards, Massenburg's impulse to salvage thus elevate -- allows a second, lingering look at people and places that have long occupied the margins of the city's larger story: "As an artist, "I wanted to relate my experience," he explains, "not to preach but to raise questions."

If you've spent some time exploring the city outside of your car in certain corners of Los Angeles County, you might have glimpsed some of Massenburg's work -- commissions or public art projects he's had a hand in -- most likely without even realizing it. It might have been the mosaic-inlayed benches at the Rosa Park's Station on the Metro ("Pathway to Freedom" -- a collaboration with Robin Strayhorn, or the stoic black fireman of another era who serve sentry to the African American Firefighter Museum on Central Avenue ("Circa 1912") These are the quiet ways the alternate narratives whisper in your ear.

"Circa 1912," by Michael Massenburg, at the African American Firefighter Museum.

His most recent large-scale installation is a series of wildly vivid mosaic panels -- that recall a scatter of photographs in a scrapbook or family album above the platform at the Farmdale Station on the Expo Line. The piece, titled, "All in a Day" is a tribute to the people and places--and their stories -- that make up the various neighborhoods spidering out just below and beyond the railway -- the stretch of track that is now re-stitching the city end-to-end -- East to West. "That's home," says Massenburg. "Everything I've done in the early years prepared me to work on this project. I was meant work on this one."

"All in a Day," by Michael Massenburg, at the Farmdale Station on the Expo Line.

While Massenburg's pieces -- explorations of history, spirit and place -- have found homes in other places across the country -- his grand installation "Jazz Era" at the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, Missouri or pieces in shows in Haiti and Senegal, commissions in Baltimore at the ESPN Zone -- Los Angeles is his inspiration and canvas. "I'm drawn to alleyways, passageways, vanishing points," he says, "the hows and whys are important;" the open-questions of a journey.

"Jazz Era," by Michael Massenburg, at the American Jazz Museum.

"All in A Day" in many ways like a compilation -- retracing his path -- physically and emotionally -- the breadth of the stories he's absorbed since moving to Los Angeles from San Diego in the early 60s. Those panels express a perspective on life in Los Angeles that often quite literally flies under the radar, remains a mystery. For many Angelenos who have lived and worked in these neighborhoods, they are a powerful antidote to erasure, they pause on those isolated moments and gesture that, pressed edge-to-edge, overtime evolve into memories.

Sunk deep into the these tableaux are bits and pieces of memory -- personal and collective -- they are moments, pauses, connections -- the faces even, are familiar from the life of the street below: Among them -- artist Dale Brockman Davis (and co-founder of the seminal Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park) and pioneering black journalist Libby Clark -- community pillars who helped shape a collection of avenues and boulevards and intersections into a neighborhood. "I wanted this piece to be like a time capsule -- he says motioning to the original panels that line the walls of the studio, "because I want generations later to know who was here and what we were like back in this time."

By Michael Massenburg

Massenburg is more than a bit of a collage himself. He has been living and working in Los Angeles for most of his life, his there-to-here narrative is far from linear, and like the work itself -- the details plucked from various places, a life-chronology that seems to play against time -- it somehow all coalesces. "I've only been doing art for about 20 years, in a serious, focused way," he explains. "I feel like I have always been on a path, a journey -- pulled toward something." Though he'd shown a proficiency in drawing and painting since childhood, he wanted to explore art beyond narrow genres or boundaries -- and let serendipity lead him. He'd been in and out of college art classes; studied, graphic design, then took a sharp turn -- shifting to the business school at Cal State Long Beach. He tabled that to focus on his own mobile DJ business with his father, "Mass Production," which sent them threading through parties, events with their dual turntable throughout the stretch of Los Angeles -- and then then spun-off yet another side-venture: designing and embroidering logos, custom clothing shirts, jackets --including the game jerseys for the Clippers.

But by the early 90s, Massenburg felt as if he were in a full-scale free-float; he was at an impasse. Did he see himself as an artist? And if so what sort? The city itself was shifting; and the frustration and fury vividly articulated in L.A. unrest of 1992 turned out to be both a catalyst and awakening for Massenburg: "I was working [ at an [art store] doing art and showing work -- but wasn't really directed. Then this stuff started jumping off. It was like: 'I do art, but what does that mean?' I look out the window and the neighborhood market is being looted. Down the street the gas station is being burnt down and I'm thinking: 'What am I doing?' I didn't want to create in a vacuum."

Those three days in April rethreaded an old, yet still-vivid memory from his youth: watching the slow progress of jeeps and trunks just across the median from his childhood home at 98th and Figueroa back in August 1965 and the Watts Uprisings. It seemed unreal: frames spliced from a movie -- or bad dream -- the cast of the sky, the bitter char in the air. The neighborhood in its own personal turmoil -- didn't seem to fit into the rest of the story of the city, or of the neighborhood for that matter -- but it would become the one event to define it. A broken place. Thirty years later, the same, it seemed, might happen -- the particulars of a day-to-day life in these neighborhoods shattered -- swept away, a secret.

By Michael Massenburg

At a philosophical crossroads, he sought consult from the artists John Outterbridge and Charles Dixon whom he'd met along his artist's journey. "It wasn't so much that they gave me answers," he recalls, "It just gave me a chance to vent and express where I was, so I was able to formulate some ideas." But just as things were beginning to clarify, he was knocked off balance. His mother suddenly took ill and died. "But during the eulogy all I heard was how proud my mother was that I was an artist -- this was before the commissions and shows and grants." She knew, it was now time he did.

He applied for, and won, a grant from part of the Cultural Affairs L.A. Recovery Fund, which enabled him to begin commissioning his own projects, teaching, as well as embarking on his own projects. "All of the things I had been doing, I began to understand, would serve me -- a lot of these things -- the teaching, the art, running a business -- were interconnecting."

By Michael Massenburg

Those vivid murals threading along library walls, the proposals he writes, the commissions he wins, the mosaic panels that rise above the train platforms, making the unknown known, were all ways of educating, of taking generations of whispered asides, of silenced truths and making them a part of Los Angeles visual -- and thus formal -- record. They make public the essential heart of private stories: "We are so stereotyped and typecast in these neighborhoods in a certain way. I wanted people to know that we are everyday people doing every day things that everyone around the world is doing -- but sometimes it would be difficult to know that."'

What he's learned is that the act of salvaging -- collecting that whispered aside, staying rooted in/mining place -- is as essential as landing the piece of splintered wood or faded signage. They are one in the same. "I remember John Outterbridge saying to me that art can be anything that you want it to be. Even your life. So when I think about how I got here -- my journey -- it wasn't a straight line, it wasn't a plan that just anybody could follow. " That picking and choosing -- finding a treasure - the assembling, "Is like improvisation. You can't plan for it, you just have to be prepared for it -- to react to the moment. That's how we've survived -- as a people. If you think about it: That's why we're still here. "

Dig this story? Vote by hitting the Facebook like button above and tweet it out, and it could be turned into a short video documentary. Also, follow Artbound onFacebook and Twitter.

Top Image: By Michael Massenburg.

No comments:

Post a Comment